From household items to medical uses, 3D printing is already enabling a wide variety of applications. While the technology has existed since the 1980s, there have been huge advances in the field in recent years, and 3D printers are now creating architecture on a large scale.

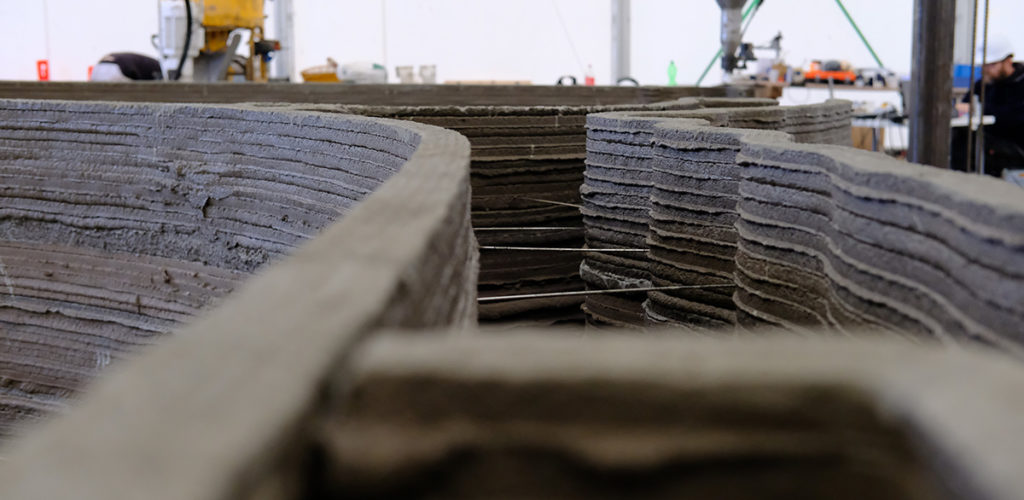

While plastic and metal were the original 3D printing materials of choice, concrete 3D printing is starting to emerge, and is expected to change the construction business in the coming years as printers become more sophisticated.

As the vital binding element in the makeup of concrete, cement and 3D printing technology are a match made in construction heaven. Cement's natural flexibility allows it to be formed into any shape, making it the perfect material for use in concrete 3D printers, and its durability gives new structures longevity and stability. Add to that low cost, and sustainability, and the possibilities seem limitless.

Needless to say, this potential has generated an enormous buzz across the architectural, construction and engineering sectors, and companies and researchers are racing to produce bigger and better 3D printed structures and buildings.

At the UK's Loughborough University, researchers have developed and patented 3D concrete printing (3DCP) technology for the manufacture of full-scale construction and architectural components.

The team's computer-controlled 3DCP printers are fitted to a gantry and robotic arm, and precisely deposit successive layers of specially formulated high-performance concrete to create complex structural components.

First European breakthroughs

It's only a few years ago that the first breakthrough for large-scale 3D printing was achieved in Europe, with the production and use of a structural element for a public space in 2016. This four-metre high structural pillar supports the playground roof of a school in Aix-en-Provence (France) and was the first of its kind to be used in a public space.

The pillar is made of two parts: an envelope, and cast concrete inside the envelope. The latter is a high-strength fibre-reinforced concrete specifically formulated for structural purposes, which was poured into the pillar's envelope to give the necessary structural resistance.

The following year, BAM Infra and the Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e) collaborated to build an eight-metre long cyclists' bridge in Gemert, The Netherlands. The bridge is constructed from pre-fabricated concrete blocks, which were printed by robots, and it was successfully tested with a load of five tonnes. The structure is, according to the team at TU/e: "The world's first 3D-printed, reinforced, pre-stressed concrete bridge."

The first fully constructive 3D-printed pre-stressed concrete bike bridge in Gemert, The Netherlands. (Photo by BART MAAT/EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock)

Europe's first 3D printed building

But, as impressive a feat as this is, it is just the tip of the 3D printing iceberg. Danish company, 3D Printhuset is currently constructing Europe's first 3D-printed building in Nordhavn, Copenhagen. It has named the 50m2 structure The BOD (Building on Demand).

The BOD has no straight walls or lines, apart from the doors and windows; its organic form showcasing the advantages of combining 3D printing and cement, to produce complex, novel structures at a low cost.

Construction of the BOD began by identifying a site to print on and developing a 3D concrete printer to European standards, say the team.

The next step was to experiment with concrete recipes until they found the ideal mix for use in the printer. The formula they opted for adds a high volume of recycled tiles and sand to the cement, which, they say, adds to the BOD's environmental credentials.

Proponents of 3D printed construction also believe that the technique can offer a quick, low-cost solution to some of society's most pressing challenges, such as providing shelter for people displaced by natural disasters and constructing homes in regions affected by housing crises.

In 2017, Apis Cor, a 3D printing company based in San Francisco, partnered with a Russian developer to print a house in just 24 hours – the kind of timeframe that would be essential in disaster response. A mobile printer was set up on-site to speed up the process and save on transportation costs. Suspended on a crane, the printer constructed the concrete walls and building envelope layer by layer. According to Apis Cotr, the construction costs were just €8,688 and the house has a life span of up to 175 years.

The BOD (Building on Demand).

3D becoming the norm?

But, despite an increasing number of challenging and ambitious projects, 3D printing still has a number of challenges to overcome before it can be mainstreamed on a large scale. The development of new skills is paramount, as 3D printing projects require know-how that is not inherent in the traditional construction value chain. And this requires the integration of new players, such as industrial integrators, robot technology providers or digital conception and software chain management experts.

Credit: 3D Printhuset A/S

Large scale adoption of 3D printing brings fundamental changes to the models of building practice and will require new skills and new entrants in a highly fragmented value chain.

As we move into the next decade, we may soon see fast-produced disaster housing, recycled skyscrapers in our cities, or even an entire 3D printed village in Italy.

But, change is coming, and the future for 3D concrete printing looks bright, particularly in Europe where around 60% of all 3D construction printing projects now occurring are actually taking place. These projects will also integrate moisture and insulation management to deal with our varied European weather conditions.

The signs are that European businesses are recognising the importance that 3D concrete printing will have on future construction projects, and are keen to be involved. The European 3D concrete printed revolution has begun.